SULAIMANI, Kurdistan Region – A brilliant, blue butterfly lives in the gorges of the Zagros Mountains. Its hue is like the sky after rain washes the dust out of the air. There are no markings on its wings, which stretch three and a half centimetres from tip to tip, save outlines of grey at the very edges. It is a rare creature, found only in the mountains that straddle the border between Iran and the Kurdistan Region, but it is disappearing, a victim of climate change.

Entomologist Farhad Khudur is an expert in the Kurdistan Region’s insect life; it has been two years since he last saw the azure flash of the polyommatus karindus.

Butterflies, like all insects, are cold-blooded. They are highly sensitive to temperature fluctuations and the health of their populations is a key indicator of climatic changes. In the Kurdistan Region, the butterflies and other insects are telling us that we are in trouble.

There is a lot we don’t know about Iraq’s insects. “The area is poorly studied,” said Khudur. “This is a good chance for me – I’m lucky,” he added with an apologetic laugh.

Foreign scientists did the initial field research of Iraq’s insects in the first half of the 20th century, during the British mandate and the monarchy. From the late 1950s to the 2000s, subsequent research by Iraqi scientists focused on economically-important insects — the pollinators and pests that determine the success or failure of agricultural crops. Scant attention was paid to documenting the full range of entomological diversity. Today’s scientists are running against the clock to catalogue the country’s insect life before it irrevocably changes.

Khudur’s fascination with the natural world began during childhood rambles in the mountains, valleys, and forests of the Kurdistan Region. He has studied insects for nearly 20 years, and in 2016 began to focus on butterflies, recording populations and collecting samples from across the region. He has documented more than 100 species, including eight that were observed in Iraq for the first time. He has also seen dramatic changes in this short period.

In the past two years, Khudur estimates that populations of common butterflies have declined by about 70 percent, while rare ones like p.kurundis, and its cousin p.peilei, have “disappeared.” Photographs he took of the little blue butterfly in 2020 may be the last record of its presence in the Kurdistan Region.

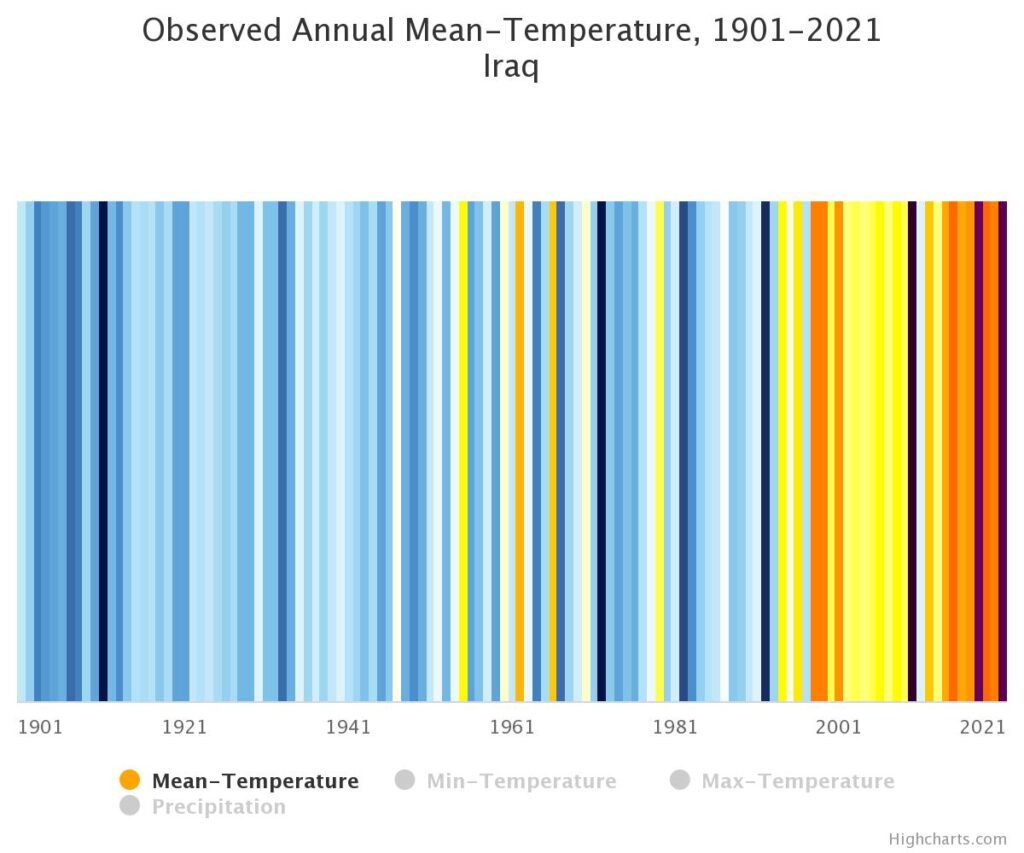

Iraq is becoming hotter and drier. Temperatures are steadily rising and are projected to increase by two degrees Celsius by 2050, while rainfall is expected to decrease by as much as 17 percent during the winter rainy season. The country’s water reserves dropped by half in 2022 compared to the previous year. Two consecutive years of drought and dust storms have devastated the country’s agricultural sector. In a recent study by the Norwegian Refugee Council, a quarter of the farmers surveyed reported a near total failure of their wheat crop.

The Kurdistan Region’s biodiversity is extremely vulnerable to the climate crisis, but other types of human activity are also undermining its resilience. The construction of roads and farms and changes to watersheds over the past decade have contributed to drought conditions. Wildfires sparked by Turkish and Iranian bombardments and airstrikes that target Kurdish dissident groups sheltering in the mountains destroy high-elevation grasslands that help retain water and provide valuable habitats for a wide range of animals.

The effect on insects is “direct and horrible,” said Khudur. Butterflies that feed on nectar and pollinate flowers while they dine lose their food source when water-starved plants wither. Bees likewise struggle to find food in a parched landscape. After frequent sandstorms in 2022, yields of honey collected from hives in the eastern mountain regions of Erbil governorate dropped by half.

“We can see the amount and the richness of insects [has] declined,” said Korsh Ararat, conservationist and lecturer at the University of Sulaimani. In spring and summer especially, he would see many different species of insects, but no longer. “Dragonflies – you can’t see dragonflies nowadays.”

Species like the blue p.karindus that live in small geographic niches are especially vulnerable to changes in their environment because they have nowhere else to go.

“Across the world… nature is on its knees”, Tanya Steele, chief executive of the UK branch of the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), said at the release of the organization’s Living Planet Report 2022.

The report estimated there has been a 69 percent decline in global wildlife populations between 1970 and 2018. This “confirms the planet is in the midst of a biodiversity and climate crisis, and that we have a last chance to act,” the report concluded. Some experts believe the earth is in the midst of its sixth mass extinction. The last one wiped out the dinosaurs.

Much of Iraq’s biodiversity is found within the Kurdistan Region’s wide range of environments, from semi-arid plains to alpine mountains. Piramagrun is a peak of just over 2,600 metres and dominates the landscape between Sulaimani city and Dukan Lake. Historically, the mountain was water-rich, experiencing heavy rain in the autumn and spring and deep snow in winter. Khudur visits the mountain many times a year, calling it a “unique habitat.” It is home to oak forests, hundreds of plant varieties including wild herbs used in traditional medicines, wild goats, birds like the endangered Egyptian vulture, and numerous species of butterfly. But drought is increasingly disrupting life on its slopes.

Piramagrun is one of the places where Khudur has spotted the rare p.kurundis and p.peilei butterflies. If water sources continue to dry up and temperatures continue to rise, the mountain will “not [have] suitable conditions for life, for all organisms,” he warned.

Protecting biodiversity is part of the government’s plans to mitigate the effects of climate change. According to Abdulrahman Sidiq, head of the Kurdistan Regional Government’s (KRG) Environment Board, an inter-ministerial committee is “studying and identifying the natural areas which in the future should be made into natural protected areas” in the Kurdistan Region.

Piramagrun is one of the sites under consideration for protected status, along with Qaradagh, also in Sulaimani, Halgurd-Sakran in Erbil governorate, and Barzan in Duhok governorate. Environmentalists have campaigned for years for these sites to become national parks, but have been stymied on multiple fronts.

The committee is working under a government regulation that was approved in 2011 and dictates the establishment of natural reserves, as mandated in the 2008 environment protection law, but remains unimplemented after more than a decade. Failure to implement legislation is a chronic problem of the KRG and, in the Region’s personality-driven politics, projects like a national park often need a powerful champion – but when that person dies, as was the case in Halgurd-Sakran, the dream of the park also fades, and green initiatives are prevented from taking off.

While some insects are struggling to survive, others are taking advantage of the changing environment and climate to find new places to live.

As Khudur chatted on the grounds of the University of Sulaimani, a pale orange butterfly fluttered by. It was a salmon Arab — named for its colour and the arid habitat of the Arabian Peninsula that it favours. When he began his butterfly study six years ago, Khudur occasionally saw the species on trips to lowland areas, but not in the mountains. At “high elevations and in dense oak forests, I didn’t see this butterfly,” he explained. “Now I can see it,” he said.

Other insects are hitching rides with animals that are on the move because of the drought. Shepherds are taking their flocks of sheep and goats further afield to find good grazing pasture, moving from dryer areas to further up the mountains where water is relatively plentiful. It is now possible that you’ll be bitten by blackflies on Mount Halgurd, where the bugs were rare just a couple of years ago.

Some new species can bring new threats. The sandfly is a bloodsucker like mosquitos and transmits the parasite that causes leishmaniasis, disfiguring skin ulcers known locally as the Baghdad sore. It is native in Iraq’s central and southern deserts, but is now increasingly found in the Garmian region on the Kurdistan Region’s southern edge.

Garmian is experiencing desertification because of reduced rainfall and upstream damming on the Sirwan River. As a result, its environment, Khudur explained, is starting to resemble central Iraq. “So it’s a good habitat for sandflies. Maybe we will find this sandfly and its parasite in the next few years here in Sulaimani, I expect that,” he said.

Changes to insect populations affect the entire ecosystem. When the rhythm of one species changes, it is thrown out of sync with the life around it. With fewer pollinators, plant populations are weaker, which means a loss of food sources for a whole host of grazers and herbivores. Populations of butterfly predators — like dragonflies, wasps, and beetles — are declining along with those of their prey. The effect continues to ripple out to humans as well, who depend on the health of ecosystems as much as any species. “This is the cycle,” said Khudur, adding that the declining populations of insects like the blue p.karindus is a warning for us to act urgently. “We need to protect their habitat diversity.”