ERBIL, Kurdistan Region — Excitement shivered down my spine as I put on my shoes and made my way to the alley where Shahad and I would always play hopscotch together in Baghdad’s Zayouna neighborhood. The sound of our laughter soared in the street as we jumped from one square to another, the wind brushing through our hair. Neither of us knew it would be our last time playing together.

It’s been twenty years since I last saw Shahad. That final, joyful moment I shared with her is not just a memory, but also a lesson in how the US invasion of Iraq deeply scarred the childhood of a generation of Iraqis and shaped us as adults.

I was born in 1998, a time when instability loomed over my homeland. News of the US readying a bombing campaign traveled at light speed, sparking fear and horror in the hearts of people, including my then-pregnant mother. My parents decided that I was going to be born before the bombs. And I was, three weeks before my mother’s due date. I had wet lungs and my nails were still not completely formed, my mother always tells me.

One month and three days later, then-US president Bill Clinton ordered strikes against Iraq, claiming that Saddam Hussein had failed to comply with United Nations Security Council resolutions and had interfered with inspectors searching for weapons of mass destruction.

Luckily, I do not remember that part, but it comes hand-in-hand with the story of my birth. Barely open, my eyes took in the uncertainty of war, locked in my skies like a heavy cloud.

In March 2003, just months before my fifth birthday, US forces invaded Iraq promising to destroy Iraq’s alleged weapons of mass destruction. Instead, they tore down the cradle of civilization, the hopes of its people, and thousands of childhoods. The weapons were never found.

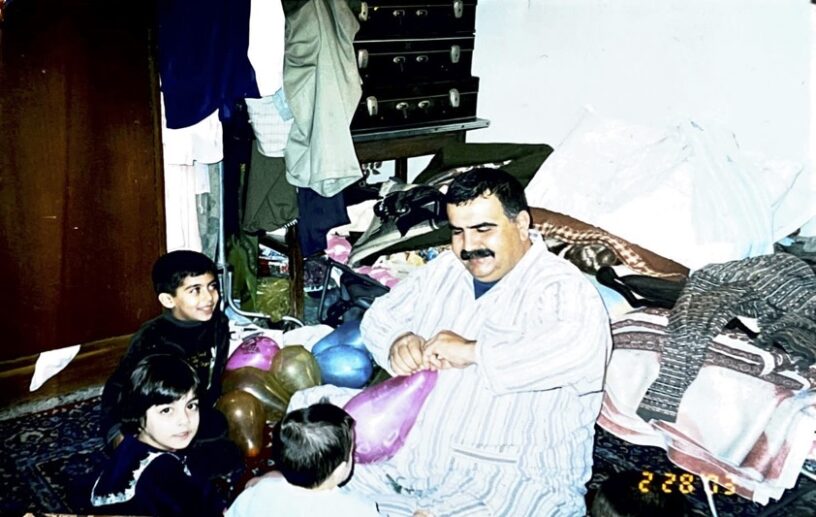

My uncle turned a room in our home into our “safe space.” He covered the windows with mattresses to protect me and my brothers from glass shards in case bombs fell nearby. We spent most of our time playing in that room, and the memory of it is bittersweet, fear tempered by a family’s love.

As war and violence pulsed through the country, my family tired of pretending to have another normal day when nothing was really normal. We started to become desperate for the light at the end of the tunnel, and there it was, standing high, bright, and beautiful. It was Erbil, where my father was born and raised.

Somewhere between late April and early May 2003, my family arrived at my grandfather’s big house in one of the oldest neighborhoods of the Kurdistan Region’s capital. It was the first place my father had ever called home: 600 square meters of free space full of welcoming men, women, and children. When we arrived, they set out long tables in the backyard, spread thick with Kurdish food and kebabs. Laughter filled the whole garden. I was so happy I thought I had arrived in heaven.

My grandfather and his family were originally from Mosul, but they spent most of their lives living in Erbil’s ancient citadel, growing a family with mixed roots. I don’t remember my grandfather much, but I still recall how he held my little hands when we used to go for walks during his visits to Baghdad.

Time passed, and the violence in Baghdad didn’t ease up. After a few weeks of big family gatherings and beautiful moments, the decision was made. We were moving to Erbil for good.

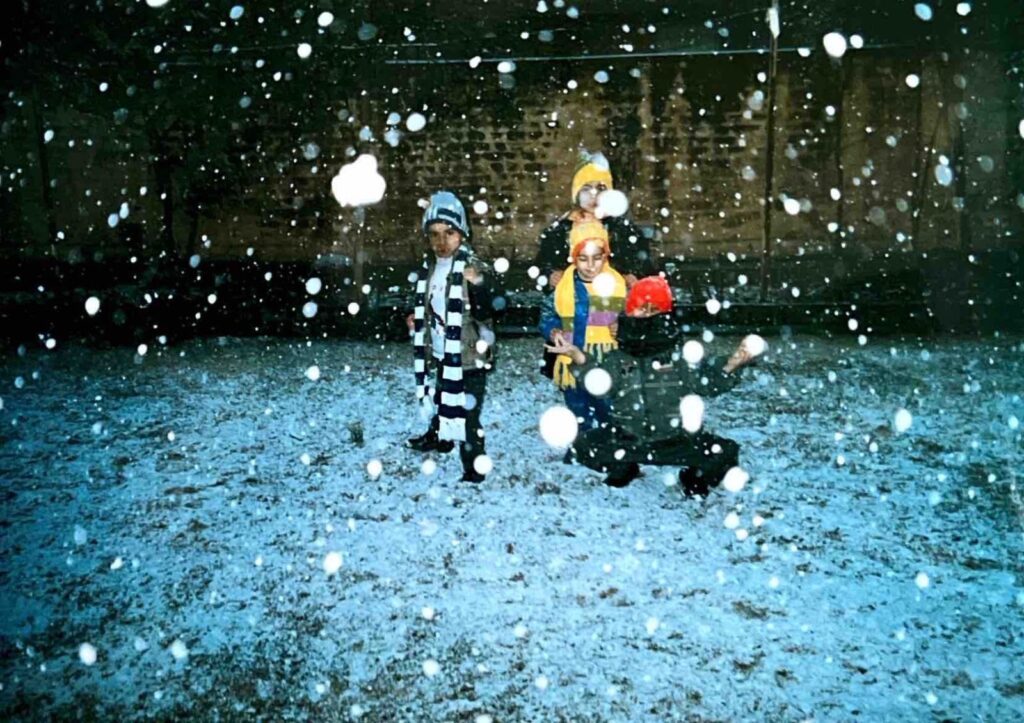

My brothers and I were ecstatic to begin a new life in the Kurdish city. We picked up the language from our surroundings and started speaking Kurdish in a matter of months. We began our education and life rushed by. But, the nostalgia I have for Baghdad feels like a knot in my throat that tightens every time the city is mentioned.

Sometimes I sit by myself and wonder: where would I be if the US had toppled Saddam and his regime without destroying Iraq and its capital? I might have had another morning to play with Shahad. I don’t even know where she is now. Sometimes, she feels like a character in my head, like an imaginary friend, but I try to think of her little curls and pink cheeks often, to immortalize the memory.

The invasion, and the instability and sectarianism that came after, pushed many of Iraq’s children out of the country and killed the spark in the eyes of those who stayed. Home should not be a place you eagerly wait to leave.

Maybe if the foreign forces had not stepped foot in Iraq, my cousins who stayed in Baghdad and I would have seen each other more. Maybe we would have been the best of friends. Maybe my mother’s friends would have stayed in Baghdad, and the distance between continents would not have cut them so deep. Maybe my grandmother would not have had to cradle her eldest grandchild as he died, shot by unknown assailants. Maybe the name of my father’s cousin would be carved on a grave of his own instead of being immortalized in a list of missing persons.

I remember sitting at my cousin’s funeral in Baghdad, the suffocating wailing of women in the air. His fiancé wept for the life she was never going to have as I quietly watched. How many other young Iraqi men were killed in the days and weeks before their weddings?

My 26-year-old cousin was shot five times, but it was the headshot that killed him. He was left on the floor to die in a puddle of his own blood, still clutching the two pieces of dried fig his mother gave him before he left the house. There were bullet holes on the walls of my grandmother’s house after the shooting, left as a reminder of how he was brutally killed.

During one of my father’s trips to Baghdad, he was abducted by a militia. I was seven years old, sitting on the floor holding onto my mother’s legs, too scared to let go. My little brother was in her arms, his eyes were so red from crying they looked like fire — exactly like my mother’s eyes. My father was let go a few hours later, but the terror felt in that moment still lingers.

I missed my grandmother’s funeral. The situation in Baghdad at the time was fragile. My mother was already in the city and my father was in the US, so there was no one to take me and I was not allowed to travel alone. I cried myself to sleep that night and remembered her words from when she hugged me for the last time, three years earlier. “God knows when I will see you again, my daughter,” she said. She never did.

Endless questions crawl through my mind. The 20th anniversary of the US invasion also marks 20 years since I came to Erbil. People sometimes say that I am just another “confused” or “split” identity, which I always take with a smile. But I am not confused.

As I grow older, I realize that I can never let go of my Arab roots, but I give them the space to mix with Kurdish culture and heritage. Erbil extended its arms to me like a mother greeting her child, and it opened my eyes to a new world. I watched the city develop and the buildings grow. I went to school here, I made friends, and I planted my Arab roots in Kurdish soil here in Erbil.

Earlier this month, I wandered the streets of Baghdad and looked at the houses that once buzzed with life. Some are empty and some have been turned into new apartments and supermarkets.

I smiled at the palm trees, which reminded me of my grandmother’s house. There was a big palm tree in the garden and in my memory the sunlight dappled through its fronds as my cousins and I played beneath its branches.

But an uneasy feeling lingered in my chest. My hometown did not recognize me and, deep down, I did not recognize it either. I was a foreigner in my hometown, an outsider who did not belong. And I cannot help but wonder: would I have felt this way if I had left Baghdad for different reasons?

There is an Arabic saying that my mother uses quite often, and I like to think that it captures my situation best. “A mother is not the one who gives birth, but is the one who raises the child”, and that is how I see Baghdad and Erbil.

Baghdad gave birth to me, but it was Erbil that raised me.