How the New York Times turned a feud between two Swedish Kurds into an international drama, a two-part investigation.

On a late summer day in 2021, Shadya*, a young Yazidi woman, was sitting in her tent in a camp in northern Kurdistan Region when her phone pinged with a distressing message. Someone had sent her a photo of two women. Her own face peered back at her, sitting next to another woman in a green headscarf who was circled as if she was a target. Then a second person sent her the same image, saying a man was looking for the two women.

Shadya had survived five years of enslavement at the hands of Islamic State (ISIS) militants before she was rescued. Living in a tent near Zakho, she thought no one was interested in her meagre life, except perhaps her former captors. The image did not scare her as she was surrounded by her family, but the message unsettled and infuriated her.

Little did she know that she was caught up in a drama created by one of the world’s largest, most reputable media organisations – the New York Times – as an investigation by the paper spun a simple feud between two Swedish Kurds into an international spectacle.

One of the two Kurds at the heart of this story is documentary filmmaker Hogir Hirori.

Born in a small village in the mountains of Kurdistan, he had survived genocidal attacks, a daring journey as a refugee, and the struggles to adapt to a new life in Sweden where he worked hard to learn the language of his adopted country and pay for film school. He honed his craft as a filmmaker and, in early 2021, dared to dream of winning an Oscar. On a gloomy October evening, however, his dreams were shattered.

That evening, he was on a Zoom call with about 30 colleagues in the US. They were discussing The Times investigation into his latest film that accused Hirori of acting unethically. “God has spoken,” he recalled someone saying, referring to the power and influence of the newspaper. Hirori’s heart sank as he envisioned this one article marking the end of his journey as a storyteller.

The film was Sabaya, a documentary about one of the most persecuted communities in the Middle East trying to rescue their women and children from the hands of ISIS in northeast Syria’s al-Hol camp in the immediate aftermath of the group’s territorial defeat of late March 2019. The film was an instant hit and received glowing reviews, including from the New York Times. In February 2021, Hirori won a directing award at the prestigious Sundance Film Festival, becoming the first Swedish filmmaker to take the prize home.

Half a year later, on September 26, 2021, Hirori could not believe when he saw his photo in the New York Times under the headline: “Women enslaved by ISIS say they did not consent to a film about them.” The article was authored by The Times’ Baghdad bureau chief Jane Arraf and her fixer Sangar Khaleel. A second article the following July took direct aim at Hirori, headlined “The unravelling of an award-making documentary.” A Canadian, Arraf had been a correspondent in Iraq since 1998, around the time 19-year-old Hirori left the country and travelled to Sweden through a network of smugglers in search of a better life.

The impact was immediate. The nomination campaign for the Oscars was gone and the International Documentary Association (IDA) cancelled a screening of the film after speaking to Arraf and instead hurriedly assembled a panel of experts to discuss the ethics of documentary filmmaking.

A Swedish tabloid, egged on by a number of campaigners, picked up on the story several months later with a two-part investigation accusing Hirori of faking a scene and turning male rescuers into heroes while they allegedly sold children to ISIS and claimed one rescuer sexually exploited female survivors.

Hirori was compared to ISIS militants and dubbed a “useful idiot” of the Yazidi patriarchy. An American diplomat long associated with the Kurdish people claimed that the film was based on falsehoods and attacked those who gave it good reviews, calling them “credulous reviewers who don’t understand the situation.” Documentary filmmakers, producers, human rights lawyers, authors, writers, and students happily lent their signatures to a well-organised campaign against Hirori calling on the Sundance Institute to withdraw the award. Most had not watched the film.

As the criticisms mounted, Hirori couldn’t sleep and he stopped socialising. His relationships with his wife and two young children started to falter.

He maintained to anyone who listened that the survivors had given their consent and he had acted responsibly. He begged journalists in Sweden and the US to investigate the allegations and speak to the survivors. A litany of media outlets placed their faith in The Times and regurgitated the piece, but none did their own probe.

A dishevelled Hirori approached me in mid-June. After several in-depth interviews and speaking to three well-placed sources who dealt with Yazidi survivors including at least two who appeared in the film, I decided to interrogate the story. “I was hoping that someone would come along and ask about Hirori,” one of the sources said when I met her in a cafe in Erbil.

Over two months in the summer, I travelled across the northern Kurdistan Region and into northeastern Syria, meeting the women and rescuers featured in Sabaya in their home villages and camps. All the people interviewed for this article including the survivors said that Hirori acted ethically, he treated them with respect, and they had no regrets about participating in the film.

This is a story about ethics of journalism and how imbuing a reporter with power and authority without proper checks can have devastating consequences. When Jane Arraf was recruited in November 2020 to head The Times’ bureau in Baghdad, the paper was grappling with the aftershocks of the disastrous Caliphate podcast by its star reporter Rukmini Callimachi. The editors, including Michael Slackman who edited Arraf’s story, pledged to cure its institutional failure and abide by its own standards of accuracy. But did they?

Abu Ghraib prison

Hirori’s journey started in 1980 in the village of Hiror, fabled for its pomegranates and figs in the lush mountains of Kurdistan. When he was born, his father was on death row in Baghdad for his affiliation with Kurdish freedom fighters. Father and son first met each other through the bars of a cell in the notorious Abu Ghraib prison when Hirori was three months old and his mother visited her husband, shaking with fear as bombs fell outside at the start of a bloody eight year war between Iran and Iraq.

Five years earlier thousands of Iraqi Kurdish families had fled to Iran and from there to Europe in the aftermath of the unravelling of a Kurdish rebellion against Baghdad. Amongst hundreds of refugees that arrived in Sweden in the late 1970s was the family of a young girl, Nemam Ghafouri, the other protagonist of this story.

As the Ghafouris settled into their new life, there was no pause in the relentless genocidal campaigns of Saddam Hussein back in Iraq. His regime depopulated the border areas and displaced hundreds of thousands of Kurds and Yazidis, Hirori’s family among them. In 1988, he used chemical weapons against Kurdish civilians. At least 182,000 men, women, and children perished in just a few short years. Saddam took inspiration from the Quran to name his genocide ‘Anfal’, the spoils of war. ISIS would use similar justification 26 years later to enslave thousands of Yazidi women and girls.

In the late 1990s, Hirori was studying music at a college in Duhok, but could see no future for himself in a land where all he had known was violence. He decided to place his fate in the hands of a network of human traffickers to take him to Europe and arrived in Sweden just before Christmas in 1999, at the dawn of a new millennium.

His talent for storytelling was clear from his final project at film school, a documentary about a young Kurdish weightlifter from his home province of Duhok that was shown 11 times on Sweden’s national public TV.

After finishing school, Hirori worked on a number of film projects and for various TV production companies in Sweden. In 2010, he married Lorin Ibrahim Berzinci, a journalist and singer who came from northeast Syria, known as Rojava to Kurds. When ISIS attacked Sinjar, the ancestral home of Yazidis, in August 2014, Berzinci was seven months pregnant with their first child.

Hirori left his pregnant wife behind and travelled to the Kurdistan Region, to the frontlines where thousands of peshmerga fighters including his father Maki who was pardoned in 1981 were holding the line against ISIS. He made two successful documentaries over the next five years, establishing himself as a serious storyteller.

The road to Sabaya

On May 4, 2019, the audience in a Stockholm library were in shock as they listened intently to the harrowing tales of a Kurdish woman who had recently been to Syria where she helped vulnerable women and children from the Yazidi community emerging from the ruins of the so-called Islamic State caliphate five years after ISIS ransacked their land and enslaved them. The survivors were badly malnourished and brainwashed, some were wounded, others were pregnant and a small number carried children born as a result of rape.

The woman speaking was Dr Nemam Ghafouri. She had arrived in Sweden as a little girl and now the 50-year-old was an outspoken humanitarian worker. She had been on the ground in northern Iraq and northeast Syria since the beginning of the genocide, assisting displaced Yazidis through her charity organisation. Dr Ghafouri was critical of big aid agencies and the UN, but praised a Yazidi grassroots organisation known as Yazidi House for their service to the rescued women.

Hirori and his wife Lorin Berzinci were sitting amongst the audience. The filmmaker and the doctor spoke different dialects of the Kurdish language, but they had a lot in common. Both came from families of Kurdish freedom fighters, were highly driven and successful, and passionate about helping the Yazidis.

Berzinci urged her husband to tell the world what had happened to the Yazidi women and children. Hirori agreed and thought Dr Ghafouri could play a role in his film.

Making the film

By March 2019, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), the force on the ground fighting ISIS in Syria, had lost over 12,000 men and women in the war. They were exhausted but found themselves in charge of more than 15,000 hardcore ISIS prisoners as well as close to 100,000 women and children affiliated with the militants, most living in the sprawling al-Hol camp. There were hundreds of Yazidi survivors in this sea of people in the camp who were so traumatised that they did not dare to make their presence known to the SDF. The fate of the foreign fighters and their families sparked intense international media coverage and many countries refused to take back their nationals, but no one really cared to rescue the Yazidis trapped with their captors, leaving the SDF to look for a solution on its own.

It was in Yazidi House that they found a partner to help identify captives and make contact with their families living in IDP camps near Duhok and Sinjar. Yazidi House was established in the aftermath of the Syrian civil war with the assistance of the Kurdish administration of Rojava to serve the 15,000 Yazidis living in northeast Syria.

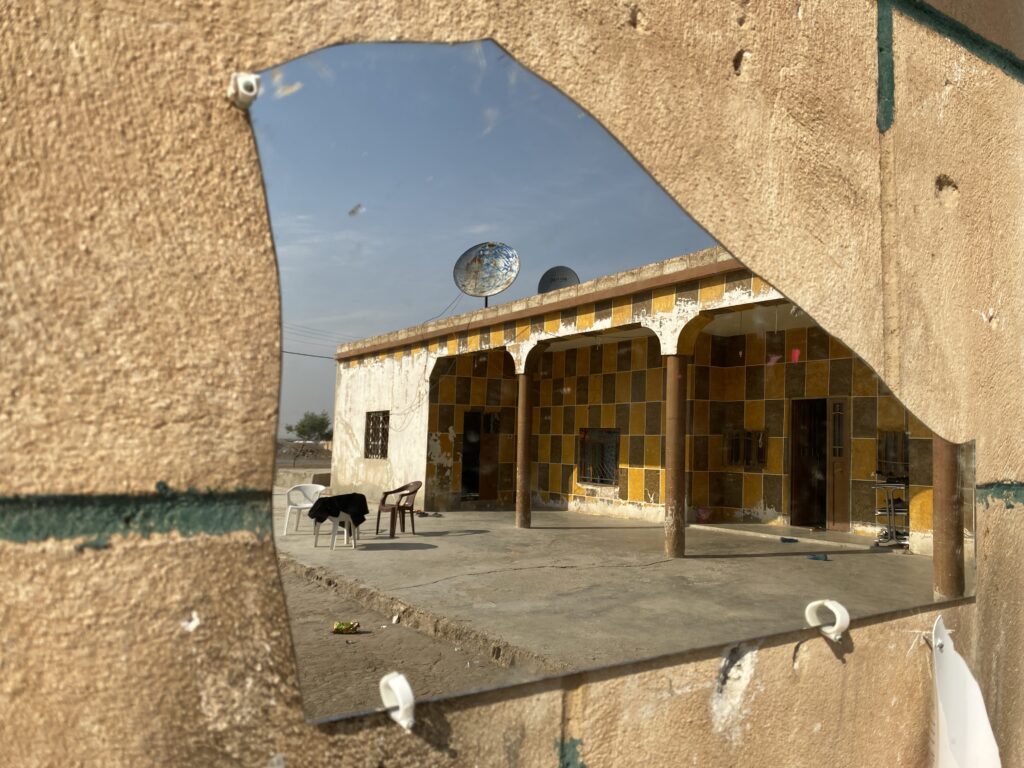

By early 2019, Mahmoud Rasho, living in a village near Hasakah, was in charge of Yazidi House rescue efforts. Rasho had cultivated an efficient network of contacts, including ISIS wives in al-Hol camp. He turned his family home into a safe house for the survivors where some would stay for a few days while others lingered for months.

Rasho was a family man and father to quadruplets. They had farm land, a flock of animals and a barn. He was of medium height with dark skin and was in awe of his mother, Zahra Kado, a matriarch who lived with them and took charge of the family’s affairs. She was extremely worried about her son’s safety going into the camp, but Rasho convinced her that this was a calling and he needed to shoulder the responsibility. The whole family looked after anyone who knocked on their door, even his sons and daughters would share their clothing with rescued children.

Kado and Mahmoud Rasho’s wife Siham believe up to 160 survivors had passed through their house by the end of 2021. Around 30 of the women and girls had children from ISIS rapists, according to Siham.

Journalists started frequenting the house, including Jane Arraf, then of National Public Radio, and her fixer Sangar Khaleel. The reporters took photos of the survivors and interviewed Rasho, then splashed the faces of the women and children across the internet. Dr Ghafouri was also always welcomed, sometimes staying for weeks at a time. Hirori arrived with Dr Ghafouri around June 27, 2019 and he too stayed with Rasho’s family.

A few days before Hirori’s arrival, Rasho and his team had rescued 24-year-old Shadya*. She is frustrated with repeated interrogations about her role in the film, feeling that her decision to allow Hirori to tell her story was being questioned. Out of this frustration, she asked for her real name to be withheld.

Like the rescue that Hirori filmed and featured in the opening scenes of his film, the night Shadya was freed was also risky, though no one was there to document it. When the rescue team entered the tent in al-Hol, Shadya was scared and did not know if she could trust these strangers. Then as they left the camp, a car gave chase and fired at them. Rasho did not tell her about Kurdish security forces (Asayesh) alerting them to an IED on the road to avoid terrorising her even further. It is believed ISIS sleeper cells inside and outside the camp coordinate with one another to target the rescuers.

The full cover Shadya was wearing was a blessing as she did not wholly grasp what was unfolding around her, she recalled in her tent in an IDP camp in Zakho.

There had been another Yazidi woman held in the same tent, but she kept quiet during the rescue. “I was too terrified to tell them I was Yazidi,” Susan* said in an interview in a village near Duhok. The chaotic scenes that unfolded around her that night were beyond her ability to comprehend after five years amongst the militants during which she had internalised the fear and come to believe that the Yazidi people had disappeared from the face of the earth. Susan would wait another few months until the rescuers came back for her.

Dr Ghafouri introduced Hirori to Yazidi House members including Rasho and another rescuer named Shex Zyad Avdal. When meeting Shadya, Hirori recalled that a year earlier in a camp near Duhok a young man had spoken about his mother, sister, and a cousin named Shadya taken by ISIS. Hirori called the young man who confirmed that the woman rescued a few days earlier was his relative. Shadya was pleased to see a friendly face who knew her family. She had many questions for Hirori about her family and how her community was faring. The two bonded quickly.

The survivors at Yazidi House were intrigued by this stranger. While journalists came and stayed for just a few hours or a couple of days, Hirori set up base and lived in the home, breaking bread with them. He came on his own with three cameras and some small filming equipment and blended in. He spoke the same dialect of Kurdish as the Yazidis and told them about his family and life in Sweden and about the previous films he’d made.

Hirori’s wife called him numerous times and also spoke to the women and Dr Ghafouri. The survivors laughed and made fun of Hirori after realising he had changed his children’s nappies. The Swedes had corrupted this Kurdish villager who came from a similar tribal background as the Yazidis, the women thought.

The women were also interested in the filming process. Hirori allowed them to use his cameras and they pretended to be filmmakers and journalists interviewing each other, Hirori, and Dr Ghafouri. “My job is to publish the stories of the Yazidis so they won’t get lost. That is my job, so no one would say that this did not happen to them,” Hirori said during one of these interviews.

They dubbed his cameras Gule (Rose), Aysho, and a GoPro was named after the sister of a survivor who was still in ISIS hands. Hirori they dubbed Abu Gule, meaning father of Rose in Arabic.

Hirori knew from his previous films working with the Yazidi community that informed consent was a continuous process and given the survivors’ experiences under ISIS, their families may object to the film and how their loved ones are portrayed. He gave out his contact details including his WhatsApp number, Facebook and Instagram accounts and told the women to talk to him if they or their families had any objection. Some would.

Gradually, the women came to trust Hirori. They opened up and started speaking about their experiences and even revealed sensitive information about their time in captivity. Photos and videos from July 2019 show a camaraderie developing between the women and Hirori, but there was a feud brewing between the two from Sweden.

Hirori questioned Dr Ghafouri’s role in freeing the Yazidis. Asayesh forces in the camp and Yazidi House staff all told Hirori that she was not involved in the actual rescue operations. Hirori decided, therefore, to remove Dr Ghafouri from the documentary. The two had a row at Rasho’s house and, afterwards, whenever Hirori tried to film the women, Dr Ghafouri was in the picture filming with her mobile phone.

Dr Ghafouri positioned herself as a gatekeeper to protect the survivors. Before she and Hirori crossed the border into Rojava, they visited the Yazidi Spiritual Council at the holy site of Lalish near Duhok where the doctor urged council representatives to establish direct contact with Yazidi House to serve the survivors better and told the religious leaders that she had influence with the survivors and they would not give interviews to the press if she advised against it. She had the best interests of the women and their children at heart, according to people who knew her well, including a number of the women she helped.

Throughout filming, Dr Ghafouri stayed on, keeping a watchful eye on the women. She passed away in April 2021 from covid-19 complications and Mahmoud Rasho died in November 2021 of a heart attack.

Hirori filmed the bulk of his documentary in late June and July 2019 with a group of survivors who had just been freed from the camp and another group known as “the infiltrators,” women who had been rescued but decided to go back into al-Hol in disguise to identify their relatives and other captives.

Children separated from mothers

One of the most heart-rending dilemmas is that faced by the survivors who carry children fathered by ISIS militants. They have to make a choice to either abandon their young ones and return to their community or stay with their children but give up the hope of reuniting with their families.

“Mahmoud always told the girls that they should do as they wished, be it to stay and raise the children or go back to their families and leave the children behind,” Rasho’s mother Zahra said. “All of them wanted to go back to their families but they also wanted their children.”

While the women and girls were received with open arms, the children fathered by ISIS remained a sticking point. The Yazidi community refused to accept them. As the numbers of these children grew, the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) set up a secret orphanage and others were adopted by Muslim Kurdish families. Two attempts to resettle the survivors with their children in the West failed. The Yazidi spiritual council issued a statement in April 2019 that appeared to suggest the women and their children could rejoin the community, but a backlash forced the council to reverse its decision and exclude the children.

The Rojava administration followed the KRG’s example and set up an orphanage as a temporary measure until a permanent solution could be found for the increasing number of children fathered by ISIS.

Hirori demonstrated this agonising decision faced by survivors in a scene where a child was taken away from its mother by two representatives of the orphanage. Everyone in the room including all other survivors, Dr Ghafouri, Mahmoud Rasho and even Hirori broke down. It is clear from the film that the mother, Sama*, did not want to give up her child.

Dr Ghafouri tried to console Sama and absolved the Yazidi community and the spiritual council as well as the Kurdish administrations in Rojava and Sinjar of responsibility, and placed blame on the Iraqi state and its constitution, which requires children be registered under the faith of their fathers. In the case of these children, they would be Muslims.

“I understand that this is your child, but there are many whose mothers, fathers and siblings were killed by Muslims [ISIS] that is why it is not fair on them too,” Dr Ghafouri told Sama in footage Hirori did not include in his documentary. “I know this is very hard for you, but they will raise your child and will not give it to anyone until a solution is found. We are trying to find a solution for those of you who want to keep their children. It will not be a problem, but you have to trust us in this.”

While Sama gave up her child, there were others who fought tooth and nail and were not parted from their children. Yazidi House provided them with temporary accommodation. One woman stayed with her two children in a house near Rasho’s village for two years. The New York Times and the Swedish tabloid accused Rasho and his team of placing this woman under house arrest. While I was in Rasho’s house, his daughter was contacted by the woman from a country in Europe and categorically rejected such a claim. Her host, a woman from Sinjar, also confirmed over the phone that the mother was free to come and go as she pleased and shared the house with them for two years, allowing her to be with her children. When the woman’s family crossed the border from Iraq to persuade her to go back to Sinjar, she refused.

Finishing the film

Hirori travelled to Rojava six times and tried to take one last trip in late February 2020 but was unable to because of covid-19 restrictions. While editing the film in the second half of 2020, he decided that Shadya’s story would drive the narrative, but he did not have Shadya’s rescue on tape and so chose to illustrate that part of her story with other footage.

“During my trips to Syria, I had been filming several rescue missions inside al-Hol, all quite dramatic. Shadya described her own experience the night she was rescued by Mahmoud [Rasho] and volunteers at the Yazidi Home Center [Yazidi House] as very similar to the ones I had witnessed myself,” Hirori explained. “When in the editing process, I chose Shadya as one of the main characters of the film. Illustrating her rescue through my own film material was an important part of building up Shadya’s portrait in Sabaya.”

The differences between journalism and documentary filmmaking have been debated for years with many believing that documentaries lie in between fact-based journalism and art where they have more creative freedom in telling stories and eliciting emotion from their audience.

With the pandemic making travel impossible, Hirori was unable to personally take his finished film and consent forms to the subjects of his documentary, so had to do all of this online. Shadya was happy with the film, but her mother advised her to take out two scenes in which she revealed sensitive information. She initially resisted this, Shadya told me. She said that she wanted the world to know about the real pain of captivity as well as the people responsible.

Another survivor, Nadia Murad, has echoed Shadya’s sentiment, saying, “I was an ISIS sex slave. I tell my story because it is the best weapon I have.”

Hirori submitted the film to the Sundance Film Festival on October 2, 2020. In the second week of December, Shadya expressed her wish to remove the two scenes and the filmmakers honoured her request.

“We took the decision to make some changes according to her wishes regarding a couple of scenes,” producer Antonio Russo Merenda told me via email. “As far as I recall it took about 10 days to make those changes in a proper way … The new version of the documentary was sent to Sundance on January the 8th 2021.”

The woman who stayed with her two children in a village nearby Rasho’s home asked Hirori to exclude her story. He duly obliged. Hirori had filmed another woman with and without niqab and even though she had given permission to use her interview without her face veiled, Hirori only used the one with the niqab. Sabaya won the top directing award in the World Cinema Documentary category on February 1, 2021, but not long after, Hirori started facing challenges.

* Names have been changed to protect their identity and their families.

This is a two-part investigation. The second half deals with allegations made against Hogir Hirori and Mahmoud Rasho, questionable methods the New York Times used when approaching survivors, and campaigns against the film in America and Sweden. You can read it here.