SHARIZUR PLAIN, Kurdistan Region – Juicy tomatoes chopped and fried in olive oil with eggs swirled through, mopped up with a piece of chewy bread ripped off a thin round blackened from the flames of the tandoor oven. This simple but delicious dish features two foods – tomatoes and bread – that are staples in the cuisine of Kurds, who are famed for their hospitality that has food at its core. But the farmers growing those tomatoes and wheat are facing enormous challenges.

Kurdistan Region is arguably the birthplace of horticulture, but in the past half century farming has come under deliberate assault from dictators and invading armies. Today, the sector is dominated by industrial agriculture and imported seeds that are not subject to quality control. The latest threat is from rising temperatures and water shortages caused in part by climate change.

These challenges, however, are not insurmountable. Solutions exist. They exist in the rich, fertile soil, in the wild plants that thrive in the mountains, and in the knowledge and traditions of the farmers like 83-year-old Hajji Hussein Rahman Rahim, who has spent his life working the land in the tradition of his forefathers to produce nourishing food for his neighbours.

His farming philosophy is grounded in the simple wisdom of understanding the environment: “I prefer the local seeds of course, the wild seeds… They recognize the soil and they don’t need to be taken care of constantly. But the ones from outside, we have to buy fertilizers and chemicals, and they need a lot of water.”

The birthplace of agriculture

In the village of Bestansur on the Sharizur Plain, there is a mound, one of many that dot the landscape. It is blocked off by a rusted fence topped with barbed wire incongruous with the pastoral surroundings. The fence is there for protection, because scrape beneath the surface and you will find evidence of some of the earliest known farming. The practice of agriculture may have started in this spot.

The archaeological site of Bestansur, meaning red garden, is an Early Neolithic settlement that is the first evidence of village life in northern Iraq. It was during this era, from 10,000 to 7,000 BC, that traditionally hunter-gatherer communities across southwest Asia became more sedentary. Instead of living on the move in search of food, they began to stay in one spot and developed farming and herding. The steppes of the Zagros region, including Sharizur Plain, were central to this transition.

The plain is a fertile, rainfed expanse bordered by the Zagros Mountains and Iran to the east, the Sirwan River to the south, and the Tigris to the west. It has ample fresh water from springs and rivers, the plains and mountains provide habitats for a range of animal and plant species, and there is plenty of stone for making tools.

The people of Bestansur took advantage of this rich environment and began cultivating legume and cereal crops that have since spread around the world. The ancestor of all the world’s wheat still grows wild here.

In the modern village of Bestansur, the descendants of the first farmers till the same soil and draw water from the same spring and hold immense pride in their history.

“One of my forefathers used to say, ‘I love God because he created me on this piece of land – Bestansur,’” said mukhtar (village chieftain) Nawshirwan Abubakir Omar, a tall man with a thin moustache, cleft chin, and prominent nose.

There are actually two Bestansur villages, an upper and a lower, and each has about 250 homes. Their oral history traces their roots back 750 years to a forefather from the Jaff tribe, El-beg Jaff, by all accounts a colourful character who predicted that some day in the future humans will invent a thing that has two wings and flies in the sky with the birds.

With every harvest, generation after generation of farmers would carefully set aside seeds for planting in the next year, nurturing indigenous varieties that thrived in their native soil. Wheat, sunflowers, chickpeas, pistachios, and tomatoes grown in the Sharizur Plain have appeared on dining tables across the region.

The 1970s brought dramatic changes. In a campaign to suppress restive Kurds, the Iraqi government destroyed more than 3,000 villages across the Kurdistan Region between 1975 and 1989. By the end of the 1980s, over 1.5 million Kurds had been forcibly moved out of their villages and into urban centres where they could more easily be controlled. Their ties with the land were deliberately severed.

Farming took another hit from war and sanctions in the 1990s. The Gulf War destroyed irrigation and electricity systems. Under the Oil-for-Food Program established by the United Nations in 1995, Iraq was permitted to sell its oil on the global market only in exchange for food and humanitarian needs like medicine. But the Iraqi government was not allowed to use its oil funds to purchase food produced domestically, so it had to import food. An estimated 60 percent of Iraqis became dependent on these monthly food baskets.

Noura Kka is an expert in seed production and an assistant professor at Erbil’s Salahaddin University. She was about 10 years old in the early 1990s and remembers when the borders were shut and the country was cut off from the world.

“People were starving,” she said. Desperate, they welcomed any food aid that was given to them. “Whatever was waste in other countries, they brought it here,” she said.

In the span of a couple of decades, the Kurdistan Region went from being producers, accounting for 25 to 30 percent of Iraq’s total agricultural output, to being consumers dependent on handouts.

The damage to Iraq’s agriculture wasn’t even close to being done. In 2003, United States forces toppled Saddam Hussein. Iraq’s main seed bank in Abu Ghraib was hit by US bombs, destroying a thousand-year-old collection.

The following year, Paul Bremer, leading the Coalition Provisional Authority that oversaw Iraq’s transition out of dictatorship, issued 100 Orders – legally binding instructions that formed the foundation of Iraq’s new economic, judicial, and political structures.

Order 81 amended the patent law and includes the following: “Farmers shall be prohibited from re-using seeds of protected varieties or any variety mentioned in items 1 and 2 of paragraph (C) of Article 14 of this Chapter.”

The result was disastrous. Indigenous varieties of plants were lost, literally blown up; farmers were banned from using the techniques they had followed for centuries; and the country was opened wide to imports.

Global seed companies essentially took over control of Iraq’s agriculture, including Monsanto, an American company known for its efforts to monopolize the world’s agriculture through its genetically-modified crops that scientists warn may harm biodiversity and have negative health effects. Monsanto also makes pesticides and fertilizers. The company, which was bought by Bayer in 2018, has paid out billions of dollars in lawsuits in connection with its herbicide Roundup that has been found to be carcinogenic.

Every year, the Iraqi ministry of agriculture produces a book listing all the seed varieties that it has approved for import. Flipping through the leaves, one name jumps out from nearly every page – Monsanto, Monsanto, Monsanto.

“These companies have destroyed the agriculture in Iraq,” said Emad al-Maroof, a plant pathologist at the University of Sulaimani.

In Bestansur, farming is still the primary occupation. They grow rice, tomatoes, barley, wheat, and the juicy watermelon that mukhtar Omar served up alongside tart apricots.

He had just finished harvesting his wheat fields. Ironically, though the first wheat ever planted was done so in the same soil, he and his neighbours typically get their seeds from Australia, Canada, or the UK.

“I buy from private companies who import into the region and sell on the black market,” he said.

This black market is thriving in the Kurdistan Region. The United Nations called it “informal” supply chains in a 2019 report. The majority of farmers interviewed purchased their seeds from local markets where the quality is uncertain.

With no quality control, farmers have to gamble every season. The year 2022 was a bad one for farmers who did not have drought-resistant seeds. In Sinjar, 84 percent of crops failed, as did 56 percent in Duhok’s Sumeil district.

Farmers have to do their own quality control. Many on the Sharizur Plain go to Khasro Jaff for advice about what seeds are good or what fertilizer or pesticide to use.

Jaff, 44, sports a scruffy beard and balding pate. He always loved to grow things and did not finish primary school before he began working full time in the field. Some 4,000 farmers share advice on his Facebook page.

“Just a few people test seeds, I can count them on one hand,” he said, holding up calloused fingers. “Myself, I buy seeds and test them for three years at my farm. After three years, I know if they are good or not good.”

He prefers to buy seeds from the Netherlands, but seeds are brought into the Kurdistan Region from around the world. Turkey, France, Australia, Mexico, Ukraine, United States, India, Italy, Canada, Russia, Jordan, United Kingdom – the list of places farmers have said they get seeds from reads like a meeting of the United Nations.

The imports are not always checked for quality. “For many years, the government hasn’t known what comes into the country,” said Jaff.

‘It’s a disaster’

The Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) is looking to the agriculture sector to be a successful business as it works to diversify the economy away from fossil fuels. In 2021, the parliament passed a law to regulate the production and import of seeds and seedlings. The law states that all imports require a license and violators could face a fine of between five and 10 million dinars and up to a year in jail.

Enforcement of laws, however, is frequently a problem in the Kurdistan Region, which is plagued by weak institutions.

Farmers said they have seen packages of seeds where the contents were not what the label indicated. They assume that somewhere along the line, somebody opened the package, removed the original contents, and replaced them with something inferior that they then sold at a higher price.

When Noura Kka visited a number of agricultural agents to see their storage facilities and learn where they were importing seeds from, she said she saw a package of onion seeds that had been relabelled. She peeled back layer after layer in search of the original information that had been concealed five separate times, hiding an expiry date four years past due.

Many of the companies doing the importing are not knowledgeable about seeds and plant breeding, according to Nariman Salih Ahmed, a plant biotechnologist at the University of Sulaimani. “This is the issue. There is no quality control, especially for… crop germplasm that’s been introduced from different sources around the world,” he said. “It’s a disaster.”

Hadi Mohammed Faraj, a farmer in Sharizur was planting a tree on the edge of his wheat field to provide a cool reprieve during long days working under an intense sun. The 59-year-old has been farming all his life.

“During the time of Saddam, it was very good. It was one hundred times better than now,” he said. Under the reign of the former Iraqi regime, farming was heavily subsidized. Saddam Hussein imposed very strict control over seeds, ensuring they were the best quality, viable for year after year, and gave them to farmers for free.

Now, every year Faraj has to buy 480 kilos of seeds to plant his eight dunams of land. Seeds from Ukraine are the best quality, he said, but the price has doubled since the war with Russia began. This year, he bought seeds off a fellow farmer and does not actually know where they came from. He is just hoping for the best.

Quality control at the border is tricky. The Kurdistan Region has long, mountainous borders with Iran and Turkey that are difficult to police. Farmers said that if a truck belonging to someone connected with one of the ruling political parties arrives at the border, it can pass without inspection. In this way, a lot of unregulated products are brought into the country.

The drive from Sulaimani city to the border with Iran loops south through Sharizur before it turns east and begins to climb into the mountains. Last summer three people were killed in a suspected Turkish drone strike on this road.

A few kilometres past the town of Penjwen is the Bashmakh border crossing. Osman Karim is an agricultural engineer working at a government office here. He said all imports of seeds must be licensed by the government and that there are no private imports being brought across this border. The government does not allow poor quality materials to cross the border and will ban imports of seeds to protect local varieties, he said.

One of the buildings in the complex preceding the gate into Iran houses Razga, a private company on contract with the KRG to do quality control at all three of Sulaimani’s international border crossings. At Bashmakh, Razga has physical, chemical, and biological labs that are among the best equipped in the country. They test any product sent to them by the government – dishwashing liquid, dinner plates, jeans, petroleum products, animal feed, flour. They also test cereal seeds for yeast, mold, and bacteria.

Saman Abdulrahman Ahmad is the scientific advisor for Razga. He estimates that at least 90 percent of materials passing through the border go through official channels, but avoiding the official routes and regulations is easily done.

“The very, very long and complicated border between Iraq and Iran is not easy to control,” he said, noting that the frontier is bridged by strong personal relationships between people, often family members, on both sides.

“I can say, sometimes it is very easy to get materials [from] outside and bring [them] into the country without any permission from the government,” he said.

Zana Mohammed Majeed is the head of the government’s agriculture research directorate in Sulaimani. He represented the province on the committee that drafted the seed law and made a face when I asked about difficulties implementing the legislation. “Why do you ask this specific question?” he queried.

After hemming and hawing he finally said, “The law will manage the import of seeds to Kurdistan. It’s a perfect law. There’s some gaps, but they have a great law to manage it.”

Companies that import seeds say they are meeting the demands of both farmers and consumers.

Agrimatco is one of the oldest agricultural companies in Iraq, established in 1953. It imports seeds, fertilizers, and pesticides from all over the world.

Though Iraq’s economic downturn and weakened dinar makes imported products more expensive, farmers still prefer them, according to Cheemin Omar, who works in Agrimatco’s Erbil office. “The farmer trusts international seeds more than local seeds because international seeds are a good type,” specially bred to “withstand difficult conditions” like drought, she explained.

When Agrimatco wants to try a new variety, it gets a sample from a trusted international company and tests it at their field station in Qushtapa, south of Erbil. If the seed grows well, the company sends the results of their testing along with all the import and origin documents to a government directorate in Baghdad, which, if they approve, registers the variety for import.

“The farmers love the registered varieties because they are more trusted in the market,” said Omar.

Consumers, especially younger generations, prefer the wider range of varieties that come from international seeds, according to Omar, who used tomatoes as an example. There are many varieties that people want to try – cherry, roma, beefsteak – each suited for specific recipes. “We import seeds to satisfy all tastes,” she said.

‘This is wealth’

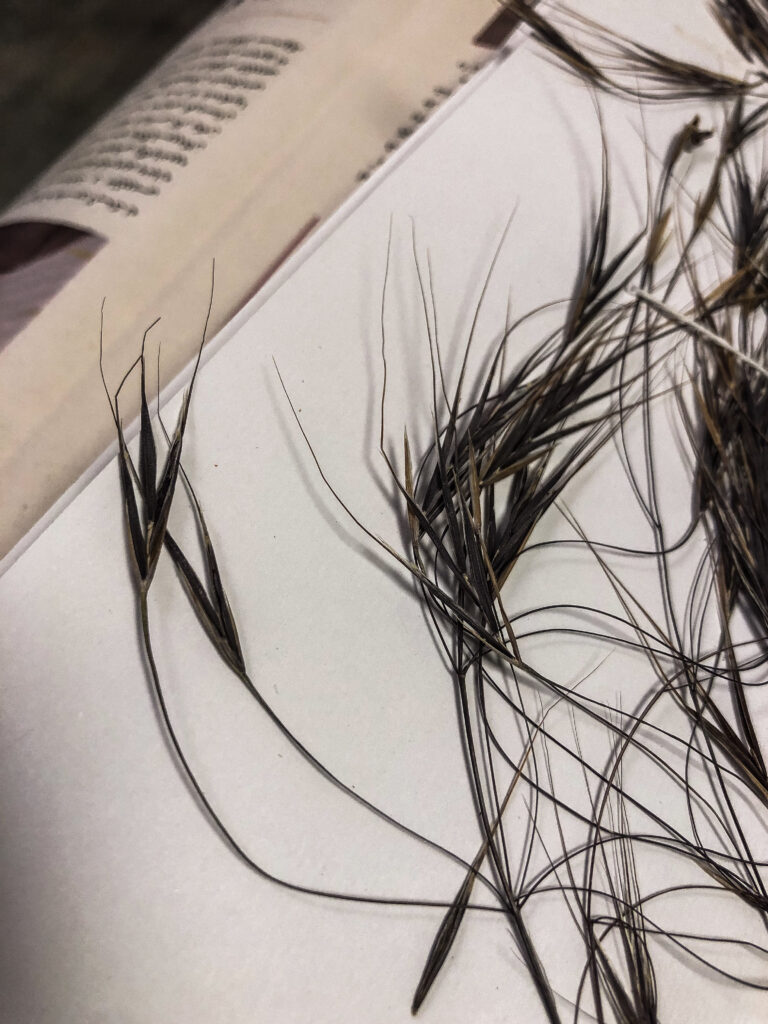

Growing wild in the Kurdistan Region are many relatives and ancestors of modern wheat and barley varieties. Aegilops “is called the grandfather of wheat,” according to Nariman Ahmed, the plant biotechnologist. It is an ancestor of Triticum aestivum or bread wheat that is one of the most widely eaten grains in the world.

Examples of Aegilops and more have been collected from the slopes of Mount Qaradagh on the western edge of the Sharizur Plain and carefully preserved by Saman Ahmed of the Kurdistan Botanical Foundation (KBF) at the American University of Iraq, Sulaimani (AUIS).

Saman Ahmed is a plant taxonomist and a busy man. In addition to advising about quality control at the border, he is president of the KBF, leads conservation efforts to protect oak forests, does intensive surveys of wild plants, and has published several field guides to the region’s flora. When we met up in KBF’s storage room in the basement of AUIS, he was giving a talk about native plants to Masters students visiting from Zakho. But he always has time to share his knowledge and love for Kurdistan’s wild plants.

Though the wild species grow in close proximity to cultivated wheat and barley, they are genetically protected. “Around 98 percent is self-pollination, it is not easy to do the cross-pollination,” said Saman Ahmed. Pollination occurs within each spikelet and does not need the help of a pollinator, which is why wheat and barley don’t need to grow flowers to attract insects.

Nariman Ahmed is a colleague of Saman Ahmed at KBF, in addition to working at the University of Sulaimani. He is also collecting wild plants and has secured a promise of funding from the European Commission to build a gene bank for native plants and seeds. He hopes to capture a picture of their genetic diversity before they are lost forever, to climate change or human activity.

“If we are able to preserve these germplasms that we consider the centre of domestication of different species, that benefits the entire humanity,” he said.

He is also studying the microorganisms that live in a symbiotic relationship with the wild wheat to know how the plants survive in the environment that they have successfully proven they can thrive in for thousands of years.

Plant roots have a dynamic relationship with microbes in the soil that are crucial for the plant to grow, stay healthy, and adapt to environmental changes. For example, several types of bacteria make nutrients in the soil like phosphorus and potassium soluble so that wheat plants can absorb them.

Nariman Ahmed hopes that learning about the microbes that wild wheat grows with will help cultivated wheat. “We can find the unique microorganism in the wild… and we can use it as a biofertilizer instead of chemical fertilizer,” he said.

There is a lot nature has to teach us. “This is wealth… [that could] guarantee food security in the future,” he said.

Similar work is being done at the government’s directorate of agriculture research on the edge of Sulaimani’s Bakrajo neighbourhood.

For the most part, the directorate gets their seeds from ICARDA – International Centre for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas – which specializes in drought-tolerant seeds and farming techniques. But two of the agricultural engineers at the directorate are bringing indigenous and wild varieties into their research.

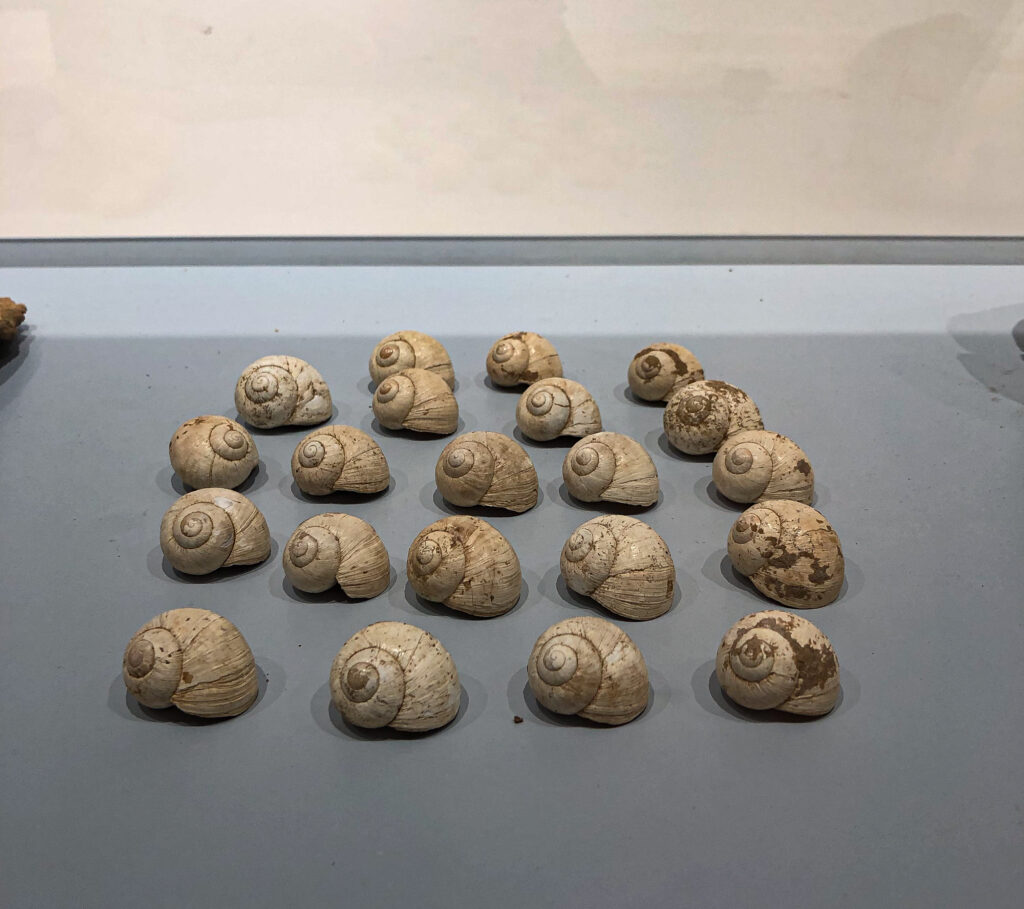

Oral Mussa Mohammed specializes in legumes and Shad Ismael Mahmud’s focus is cereals. They proudly showed me a cold room housing a collection of indigenous seeds that they have been building for seven years.

Mahmud is comparing ICARDA wheat varieties with indigenous types and Mohammed is trying a new breed of pea that he created crossing ICARDA seeds with wild ones that the two foraged about 20 years ago, the one time they were given the approval to do such research using some money left over from a different project.

Mohammed has grown eight generations of his peas and expects that in another two or three years, he will be able to announce a new variety and get it certified.

This research, however, is not supported by the directorate or the government, which does not encourage creativity. “They want you to come to your directory and sit in your chair and work in the directory,” said Mohammed.

“That’s right,” Mahmud chimed in. “Everything that we see in our country is about money, just money, petrol, and money.”

The challenges presented by climate change will require creative solutions that will only come from giving free rein to researchers like Mahmud and Mohammed.

The farmers also need some convincing. “Farmers don’t believe us because we are also from this country,” said Mahmud, explaining that farmers do not have faith in the knowledge and skills of their fellow Kurds and prefer to put their trust in the hands of foreigners.

Emad al-Maroof has the same problem gaining farmers’ trust. The relationship between farmer and scientist is one that grows alongside healthy crops supported by local research.

Maroof has been doing agricultural research for 40 years. He began in the 1980s in Baghdad, working on improving wheat resistance to the stresses of salinity and drought, as well as disease. The cultivars he produced through breeding programs were developed from landraces, the traditional varieties that have naturally adapted to their local environment.

He experimented crossing the landraces with imported varieties that have disease resistance. He has also done irradiation, exposing seeds to gamma rays that cause genetic mutations and thus create new variations. Every seed reacts to the gamma rays differently and unpredictably, but Maroof said they have gotten some good results.

He registered dozens of wheat, barley, and rice varieties, including the Maroof, a wheat cultivar descended from a local variety and a landrace.

While many seeds were lost in 2003, Maroof was able to save some of his cultivars. Seeds were stored in stations across the country and so survived. Some researchers kept caches of seeds in their homes, a practice Maroof continues today because he feels this is the safest place for them.

At the height of Iraq’s post-2003 sectarian conflict, Maroof was still in Baghdad. Many of his family members had been killed in the violence and his wife feared for their son’s safety, so they made the decision to move to the Kurdistan Region and Maroof began working at the University of Sulaimani. He is based at the university’s research station in Bakrajo, next door to the government’s centre.

In the field, he has rows of test crops. He is doing trials of a rust-resistant variety of wheat. Rust is a wide-spread fungal disease that attacks cereal crops and has ravaged fields in the Raparin district this spring.

Maroof still gets regular requests for seeds from farmers in southern Iraq where he had built up a strong network. This year, especially, he has been flooded with requests, more than he can manage, because imported seeds are more expensive for farmers paying with a weakened dinar.

He is slowly building relations with Kurdish farmers. A couple of years ago, there was very little rain and fields across the country were dry, but Maroof’s drought-resistant varieties fared well. In his office, he pulled up a video a farmer had sent him of lush wheat growing out of cracked, dry earth.

Maroof is beginning a new project in collaboration with Minnesota University. “We are trying to introduce our wild type wheat into our local varieties, because this wild type evolved with the rust diseases, so it has a good gene pool for resistance. So we are trying to transfer this gene pool into our landraces,” he explained.

The wild varieties are not suited for cultivation because they have very low yield, but traits like their resistance to drought and disease could be very beneficial.

‘Clean, natural food’

Row upon row of greenhouses fill the horizon in the Bazian area outside of Sulaimani city, evidence of the focus of industrial farming. Agriculture as industry values yield above all else, prioritizing it over things like soil health, and has led to an alarming decline in crop diversity.

Since the 1900s, the United Nations estimates that we have lost 75 percent of crop diversity as farmers abandon indigenous varieties for uniform, high yield monoculture. The food we eat has fewer vitamins and nutrients compared to just two generations ago, and the majority comes from just 12 plants and five animal species.

There is, however, a growing global movement towards more sustainable agriculture that believes the key to a healthy future lies in the traditional farming practices and localized food supply chains that work in harmony with nature.

Food & Heritage is a part of this movement. The project has a research garden at the Kurdistan Institution for Strategic Studies and Scientific Research and is part of the Rosa Luxemburg Foundation’s Gwez u Nakhl network that unites farmers from across Iraq and the Kurdistan Region who want to preserve traditional seeds and farming practices. Gwez is Kurdish for walnut and nakhl is Arabic for date palm.

On a bright afternoon, the Food & Heritage team leaves their offices to work in the garden, enjoying the warmth of a spring sun as they get their hands dirty on a hillside on the southeastern edge of Sulaimani. When I visited, they were weeding the peas, munching on fresh dill and the occasional accidentally-picked pea flower that is a surprising burst of flavour.

“It is really about food sovereignty. Kurdistan was the breadbasket of all of Iraq. It was mostly agricultural land. Everything that you see around here used to be agricultural land,” explained Shenah Abdullah, project supervisor. She gestured to the apartment towers on one side and a view of the Tanjero industrial zone on the other.

Abdullah is a social anthropologist who was studying the impact of international interventions on the Kurdish way of life. She had many conversations with people across the region and everywhere she went, the topic of agriculture always came up.

“No matter what you talk to them about, they return to the stories about what we used to grow and the food that we used to have, all about communal, everything communal. And they also talk about all the values they have lost and they connect it to coming to the cities,” she explained. “It comes up in all the interviews I used to do and it was always in the back of my mind, maybe that’s really the topic I should be working on.”

One of the largest interventions on Kurdish life was turning from agriculture to oil. It’s a relatively recent change, one made in the past few decades, yet the agricultural traditions are ancient and she hopes they can be returned to, the system can be reversed, helped by consumers who are increasingly demanding organic, locally grown food.

Some of the seeds in their garden came from a Lebanese cooperative, Buzuruna Juzuruna, that promotes heritage seeds and has built up a collection from across the region, including Iraq, that it got from local farmers and seed banks.

Last year, Food & Heritage planted Iraqi heirloom wheat that they got from a seed bank in Germany. From the original four kilos of seeds, they were able to give 22 kilos to a farmer to plant on a larger scale.

“We want to give it to farmers so we can have heirloom seeds or open-pollinated seeds instead of the imported seeds that farmers all, without any exception, depend on right now,” Abdullah explained. “And it’s food. It’s not just seeds. It’s also clean, natural food for anyone. For people who are suffering or ill, this actually is medicine for them. Non-chemical fertilizer grown food is medicinal as well.”

As we spoke, a man walking by stopped to ask if he could harvest a plant he saw growing in the garden that is traditionally used to treat cancer.

Food & Heritage is also doing an oral history project, collecting the stories of farmers, learning their traditional methods and sharing that with other farmers. As they visit remote areas, the team are finding villagers who are planting the same seeds they have been growing for at least 30 years.

“A lot of the farmers we meet say my father, grandfather actually had a little hole somewhere and saved these seeds,” Abdullah said. Seeds were secretly treasured and hidden away like contraband that was illegal under Bremer’s orders. They were passed down the generations with the knowledge that seeds mean life.

Food & Heritage is hoping to see these farmers share with each other and establish a seed library that is free to access and keeps the seeds in the farmers’ control.

Mid-afternoon, the weeders take a break for a quick lunch cooked on a portable gas stove in the garden. We eat in the shade of a traditional reed roof like the one seen on the Food & Heritage logo and are joined by an important member of their community, our wise farmer Hajji.

Hussein Rahman Rahim lives nearby and has a garden next to Food & Heritage. He walks with a back bent by a lifetime of physical labour and every day he slowly makes his way over to have a glass of tea with the Food & Heritage team who call him Hajji, a title of respect given to Muslims who have made the pilgrimage to Mecca.

He grew up in the mountains on the border with Iran. “From the time I started thinking, I have been farming,” he said.

When he was young, they had no food apart from what came from the land. They grew grains – wheat and barley – and kept animals, and foraged wild plants. Vegetable seeds only came to their village in 1962.

One of Hajji’s prize possessions is his seed collection – an assortment kept in small, carefully wrapped pieces of fabric of plastic. He gingerly opened each package, poured the seeds into his weathered palm, and showed his eager audience. This is the wealth of his lifetime of working the land. He has built the collection over the years, some come from his village, others he has acquired more recently, including from Food & Heritage. “So now we have credibility,” Abdullah said with a smile, acknowledging Hajji’s recognition of their efforts.

Hajji says his tomatoes taste better than the ones on offer in the bazaar. An indigenous variety of tomato that is irregularly shaped, puckered, folded, thin-skinned, and difficult to preserve – but full of flavour.

“There’s a big difference. My tomatoes are a bit sour, they taste good. You don’t have to add anything to it. You don’t even have to add salt because it has the natural taste. But the one in the bazaar, it lacks all these things and you have to eat it with salt to have some flavour,” he said.

Hajji laments that the younger generations of farmers do not value the traditional varieties the way he does, but prefer imports. He has argued this point with other farmers, including his nephew, pointing out the problems of growing crops using chemical fertilizers. “They don’t listen to me if I tell them these things, but they listen to the foreigners,” he said.

Hajji’s knowledge is ancient. It has been learned from the land and been passed down through generations. He is keen to share it, if anyone is willing to listen.